| Published in the December 2001 Issue of Anvil

Magazine

Note: Images and captions are at the end of this article. Everyone owes a part of his time and money to the business and industry in which he is engaged. No man has a moral right to withhold his support from an occupation that is striving to improve conditions. -Theodore Roosevelt Urged by this philosophy, Lee Liles can walk with visitors and explain the importance of treasured artifacts in the National Museum of the Tools of Horse Shoeing and Hall of Honor, which he describes as the largest collection of such tools in the world. It is a walk back into history and a return to the present. Horses and mules contributed a vital part to the development of America, especially in settling the West. The animals played such an important role in the American Civil War that high-ranking Union officers demanded that troops seek and destroy Southern blacksmith shops on which armies at that time depended. Soldiers in blue carried out their mission of destruction. They promoted an end to the conflict when they found and destroyed the tools that kept Confederate troops supplied with the absolute necessity of food and supplies. Complying with the order, invading Union soldiers pounded on the horn until they separated it from the anvil, thereby denying further use. And then they grabbed the much-wanted nails. As important as the blacksmith was in keeping the harness horses and pack mules safely shod, "his craftsmanship was just as vital in keeping the wheels of wagons rolling safely," Liles explained. As pioneers moved westward, one of the first businesses to appear was a hardware store with blacksmith supplies, and next a blacksmith shop. A hotel and restaurant followed, along with a Western saloon and place of entertainment, outbuildings, a livery stable, a courthouse and a jail. Other business establishments were added as the need and demand arose. The visitor finds this idea suggested in a subtle manner in the background in a spacious section of the museum. "Most blacksmiths shod horses and mules as part of their primary work with hammer, anvil, and forge," Liles explained. "Other craftsmen avoided general work of the smithy, became farriers, and limited their work to care of the animals' feet. The two most important needs of the blacksmith and farrier are hammers and anvils," he said. The latter he numbered by the dozens. One of those anvils Lee can boast about as being the largest in the world. He knows, because he designed it and had it cast, "just so I could say this museum has the largest in the world!" He can compare that enormous size to the smallest, which weighs in at 63 pounds. The cost of shipping heavy anvils by wagons was enough to encourage users in many states to design and cast their own version, using local materials if available. By tapping each with a hammer, Liles demonstrates how each anvil responds with its individual ping, ping, ping tone. Variation of sounds is made possible by the different materials and method of casting. The collection in one area of 105 anvils includes 56 designed for the farrier. One display is composed of horseshoeing anvils of less than 40 pounds. The oldest is a Fisher, cast in 1889. An English carriage anvil, which dates back to 1830-40, sports two horns, each shaped for a special need. Variations in the form of the anvil's horn make up another part of the collection, and these also were designed to serve a special need. Years ago Lee learned in competition that other craftsmen who care for the hooves of horses and mules had something he did not have. And when he learned it was a Champion farrier's hammer, he sought one. The search was so exciting he continued, and can show 27 of that favorite of all horseshoe hammers, a collection which he describes as the world's largest. The search proved so thrilling that after Lee found what he wanted, he just kept on looking. "I still thrill when I find something few others have," he said. Throughout the walk through the museum the visitor is aware of the arrangement of tools as the touch of a discriminating artist. The museum also contains two different styles of trip hammers, foot- powered and mechanical. Various sizes of hammers include a 20-pound sledge, one which would have demanded the best even of the village blacksmith who was praised by the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his well-known and nostalgic poem, "The Village Blacksmith." (See Anvil Magazine, September 2001.) In it he wrote: "And the muscles of his brawny arms are strong as iron bands." To overcome cold iron's resistance to pounding into shape, heat from the burning forge is called upon to make the metal pliable. That means a forge. Air must be forced through burning coal or coke to produce the desired heat that makes metal pliable. The first of the fire enhancers were huge bellows. When handles were pulled together, the device forced air through the forge, spurring the burning coal or coke into action. The simple device served for generations until someone developed the bellows of dual action, providing a constant flow of air. That gave way to the hand-cranked blowers. Today the operation is made efficient with the electrically powered rheostat to supply and control the flow of air to feed the fire. It speeds up the process of preparing the metal. One of the early ones on display is dual action. The bellows on display at the museum served the English smithies eons ago, but has been well preserved. And it was the roar of the bellows that attracted school children to "look in at the open door," in Longfellow's poem. In addition, many forges have been selected for display in the museum. Hundreds of tongs are included, each designed to grasp and hold a particular piece of metal. All are products of the smithy, the forge, the blower, the hammer, and the anvil. Care of the feet of horses and mules which served the cavalry demanded remedial work on extended assignments when away from camp. That meant forges and anvils had to be designed to be taken across the prairies in wagons or fastened to the backpacks of mules when traveling over rough country. Their design and weight required careful attention. They had to be compact and the weight held to a minimum. Animals receiving surer footsteps with new shoes were sometimes reluctant to permit the farrier to scrape or pound on its hooves. They demanded special treatment, so the unruly animals were forced into stocks. The devices developed for safety of the farrier consisted of a machine designed to lift the animal with leather straps or a blanket placed under its stomach. The horse or mule was then raised to clear its feet to prevent it from applying its strongest offense as a means of defense, the kick. Two such blacksmith helpers are preserved at the museum. Liles describes one of them as the product of a genius. It is the Arcus, made in Indiana in the 1900s, and Liles takes delight in pointing out all its good qualities. Arcus stock is the product of devotion to perfection, possibly by more than one person, and improvements employed gained from time and experience. If development of the country depended upon the wagon wheel, along with well-shod horses and mules, keeping the wheels turning was one of the blacksmith's major tasks. The museum has preserved some of those along with the tools that were developed to keep them rolling. One of those is the rim shrinker. With time and wear, the wood dries and contracts, causing the metal rim to fall away and the wheel to collapse. But before it could be applied, the blacksmith had to use the traveler, a wheel-bearing number which served to measure the inside of the metal rim. Grasping the handle which guides the circular tool, the blacksmith marked a point on the inside of the rim, and noting the number, rolled the traveler along the inside of the metal around until he returned to the starting point. Using the same method, the blacksmith marked the spot, noted the number, and rolled around the outside of the wooden wheel. The inside measurement of the metal must be slightly larger than the assembled parts of the wooden wheel. To complete the union of wood and metal, the blacksmith had to cover the metal with firewood and heat it until it expanded beyond the circumference of the wheel. He would then lift it out and, with light taps, returned the rim to the wheel. As the metal cooled and contracted it pulled the wheel together, making it a compact unit. It was not a complicated operation, but it had to be accurate. Along with other tools of the blacksmith and farrier, the museum of 4,000 square feet displays several panels of different styles of horseshoes. One board of shoes which is prized was put together in 1893. Along with it appears one of nickel-plated shoes and another of shoes made of stainless steel. There is also a collection on loan of corrective shoes. (see page 31) Most of the shoes came from the forge, hammer, and anvil of the blacksmith, either to satisfy a discriminating smithy or because shoes from the manufacturer were unavailable or too costly. And many hooves needed corrective measures; therefore, the need for special fittings. Other tools include shoe benders and clippers. Hundreds of swages make up another collection. With the metal tools the blacksmith can heat and pound a piece of metal to conform to a desired shape. Any number of swages may be used, depending upon the desired form. They may be applied either above or below the heated piece of metal and stamped into soft material. Many oddities include toe and heel caulk, a cone mantel to curve shoes, special tools for harness horses, a display of devices for dental care, ice chains for hooves, leather galoshes to protect the feet from severe weather, foot gauges to measure the angle of hooves, sharp cleats fastened to the shoe to ensure sure footage on ice, wide shoes for snow, and a Swiss Army horseshoe with sixteen nails. The museum pays tribute to those institutions and men who furthered the ancient trade which has endured into the 21st century. One of those honored is Henry Ashworth of Cornell University, who offered courses in craftsmanship for blacksmiths and farriers beginning in 1913. His teaching and writing contributed to great improvements in the ancient trade. Liles points out that such famous inventors as John Deere, Studebaker, and Henry Ford launched their careers as blacksmiths. Others who receive special attention at the museum include Heller Brothers Tool Company; four generations of design and manufacturing by Champion-Dearment families; the Kinney family; Dale Sprout; George Ernest and Jay Sharp; and to Dr. Doug Butler, who for 30 years contributed to accumulated knowledge with lectures, books, and tapes. The world's largest collection of the tools of Horseshoeing and Hall of Honor also preserves what Liles describes as "the world's largest collection of printed and tape- recorded history on the subject." The library contains 300 publications that go back to the 1700s, 20 years of ANVIL Magazine, Farmers Journal going back to 1975, many catalogs of horseshoeing products, and drawers of artifacts recorded for many years. While taking a break during the tour, the visitor may rest, listen, and look at one of the many tapes that cover various aspects of care of the feet of horses. "Artists, photographers, and poets have always been able to find romance in the blacksmith shop," he said, and careful attention is paid to those artists. Displays include walls covered with original drawings for magazine covers, paintings, and photographs. Americans are free to claim professional status as farriers without certification as to competency, and only Illinois sponsors a union. On the other hand, Europe has registered and certified farriers since 1346 and the first farrier organization there was incorporated in 1764, Liles said. However, all is not in the past. Today, of a population of nine million horses in the United States, 25,000 are shod daily by farriers. There are approximately 27,000 farriers in the U.S. and ten percent of those tradesmen are members of the national association (The American Farrier's Association) that shares and promotes improved methods and tools of the craft. Today the farrier, equipped with the latest in technological development, goes to a barn to care for the needs of horses' hooves. The men and women of the forge, anvil, and hammer also gather to exchange ideas, to compete with fellow craftsmen, and to demonstrate the finer points of skilled horseshoeing technique. Equipment may consist of a truck fitted for the purpose, or the farrier may travel light and confine his equipment to a special trailer. The ancient blacksmith or farrier would be amazed at the sight of a modern rig. Lee Liles and his wife Alma have spent many hours renovating the former brood mare operation to display their traditional and contemporary equipment at Carrousel Ranch on Highway 177, eight miles north of Sulphur, Oklahoma.

What was the driving force that spurred the search and acquisition of all

the unusual tools of the trade? For that answer Liles points to a framed

quotation from former president and inveterate outdoorsman, Theodore Roosevelt:

"Everyone owes a part of his time and money to the business and industry

in which he is engaged. No man has a moral right to withhold his support

from an occupation that is striving to improve conditions." |

|

| Captions Lee and Alma Liles at entrance of museum |

|

| Katherine and Jim Poor, farriers from Midland, TX, combine efforts to create a copper horseshoe while visiting the museum |

|

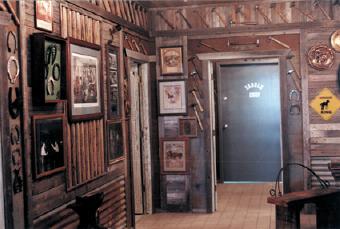

| Part of the museum's collection of farrier art, anvils and tools |

|

| Lee Liles points to his collection of champion horseshoe hammers, the quest of which led to his collection of tools for horseshoeing |

|

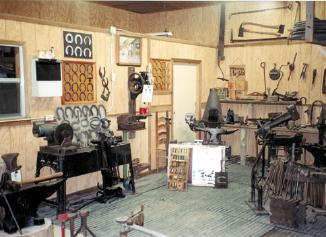

| This wall of the museum shows the history of the farrier tool companies still in existence to this day |

|

| The museum has the country's largest collection of horseshoe hammers-some of them are seen in this photo |

|

| The museum has a total of 105 anvils, 56 of these were designed for the farrier |

|

| A few of the many panel displays of horseshoes-they include nickel-plated shoes, stainless steel, and a collection on loan of corrective shoes |

|

| Some of the beautiful farrier artwork and other equipment Note the old forge in the background |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Return to the December 2001 Table of

Contents

Return to the Farrier Articles page

|

|